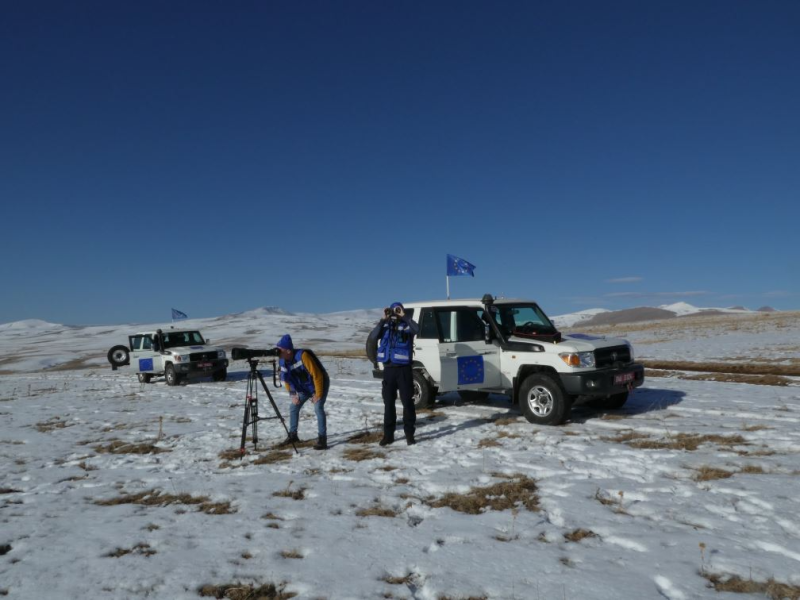

This week the European Union deployed its unarmed monitoring mission in Armenia with a mandate for two years.

EUMA - EU Mission in Armenia - was formally established by a Council Decision on 23 January 2023. According to the EU, “through its deployment on the Armenian side of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, it aims to contribute to stability in the border areas of Armenia, build confidence and human security in conflict affected areas, and ensure an environment conducive to the normalisation efforts between Armenia and Azerbaijan supported by the EU.”

The exclusively civilian staff of the EUMA will number approximately 100 in total, including around 50 unarmed observers. The mission’s operational headquarters will be in Yeghegnadzor, in the Vayots Dzor province of Armenia. EEAS Managing Director of the Civilian Planning and Conduct Capability (CPCC), Stefano Tomat, will serve as the Civilian Operation Commander, while Markus Ritter will serve as the Head of Mission. Ritter is a former German police officer with extensive international experience.

The deployment of the mission is a bold step.

For decades the European Union kept aloof from the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict, allowing the OSCE Minsk process the monopoly in seeking a resolution to a conflict that destabilised the entire South Caucasus region and hindered progress and development. After the 2020 44-day Karabakh War, the EU became much more proactive in supporting the normalisation of relations between the two countries, and the establishment of a wider peace in the region.

Since December 2021, the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan met several times through the mediation of European Council President, Charles Michel. The peace process has not been without problems, and throughout 2022 peace talks alternated with incidents on the ground. It was after one such incident that the first EU presence was deployed in October 2022, in the form of a temporary presence of a few weeks, provided largely through personnel from the EU mission in neighbouring Georgia.

The decision to deploy a longer term mission is a bold step on the part of the EU. It is necessary and underpins the EU commitment to long term peace in the region. But it would be wrong not to mention that the mission is fraught with risks, which need to be managed, including the following:

1. The risk that the EU is seen taking sides

Because the mission is deployed on the Armenian side of the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, there is a risk that the mission is seen as part of Armenia’s effort at border protection. The EU was also willing to deploy on the Azerbaijani side of the border, but Baku was not interested. Azerbaijan had, at the summit in Prague in October 2022, acquiesced to the temporary EU presence. This time it has not. Official Baku has made some mild negative comments about the mission, but pro-government media in Azerbaijan have been much more harsh in their criticism.

In its work the mission needs to quickly secure the trust of all sides. The EU insists that the mission is neutral, and that neutrality needs to be adhered to meticulously. There must be permanent dialogue between Brussels and Baku on the work of the mission in order to avoid misperception. In the end both Armenia and Azerbaijan need to be convinced that the mission is an important tool in support of their quest for long-term peace in the region.

2. The risk that the Armenians will be disillusioned

After the military defeat in the 2020 War the mood in Armenia has been swinging from one direction to another. Most Armenians feel let down by Russia’s failure to support them in 2020 and since, despite the fact that Armenia is in a military alliance with Russia. Some have spoken openly of the need to replace Russia and the CSTO with NATO and the EU. They see the mission as a step in this direction. They are wrong. An unarmed mission of fifty monitors and fifty support staff is hardly the way to provide hard security. The mandate of the mission is not to support Armenia, but to monitor the situation on the border.

This may - in some circumstances - provide Armenia with some political comfort, but that is as far as the mission will ever be able to go. But in Armenia expectations appear to be much higher, and this will inevitably quickly lead to disappointment. This will become evident quickly next time there is an incident, when the question will be asked “Why didn’t the mission intervene?” or at least, “Why did the mission not make a public assessment?”.

One can anticipate that those forces in Armenia who would like to see the image of the EU tarnished will quickly use the moment to whip up anti EU hysteria. This risk needs to be addressed through solid communication of the role of the mission to the Armenian people. It will not stop the disinformation, but at least it will mitigate its impact.

3. The risk of incidents with the Russians

The Russians are omnipresent in Armenia. They have a large military base in Gyumri, border guard elements on the border with Turkey, a heavy FSB and GRU presence, and a military force next door in Nagorno-Karabakh deployed after the 2020 war. One would have thought that with all these tools at their disposal the Russians would not be bothered by an unarmed European mission of less than a hundred persons. Unfortunately Moscow has decided to perceive the mission through the prism of geo-political competition. It has condemned its deployment in strong language.

Brussels is right in taking the time to explain to Moscow the purpose of the mission, but this does not exclude the risk of incidents on the ground. No doubt the mission will have strict standard operating procedures about avoiding as much contact as possible with the Russians. In case of incidents it is expected that the Armenian military will be available to smooth situations. But the risk of incidents cannot be eliminated completely, especially if the Russians decide it suits them to provoke such incidents as part of their wider geo-political machinations.

4. Iran’s proximity should not be forgotten

EUMA will operate close to the Iranian border (although monitoring the border itself is not part of its mandate). Iran has also recently opened a Consulate General in the South of Armenia, where the mission is expected to be active. In the current volatile situation around Iran this proximity brings its own risks, which can be managed with strict and precise standard operating procedures.

5. European politicians need to be measured when talking about the mission

There is a risk that the mission can be impacted by European politicians speaking about it out of turn or out of context. The mission is part of the EU common foreign and security policy and is therefore a legitimate topic for reference by politicians at both the national level and at the EU level. European politicians need to be measured and discreet when referring to the mission to avoid putting the mission members at risk.

6. The EU needs to avoid mission creep

EUMA has a precise mandate and set of tasks. Its leadership should ensure that there is no mission creep, and that will require a clear vision and a firm approach, particularly through moments of tension or crisis.

An important step

Despite these and other risks the deployment of this mission is necessary.

The South Caucasus is a region of great importance for Europe and the EU needs to show that it is committed to its peace and stability and will engage with all its tools at its disposal in support of such an objective.

The mission will give some comfort to the Armenian people who in the last couple of years have been feeling particularly vulnerable. This need not be at the expense of the Azerbaijani people. Avoiding incidents and misperception is in the interest of all the sides.

In the end it must always be kept in mind that the mission is not an end in itself. The quicker it becomes no longer necessary the better, for the objective is not to have an EU mission in Armenia, but to have peace between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, and in the rest of the South Caucasus.