On Friday (10 March), it was announced in Beijing that with the mediation of China, Iran and Saudi Arabia had agreed to end decades of hostility, re-establish diplomatic relations that had been broken in 2016, re-open embassies in their respective capitals within two months, and work towards resolving all disputes between them through dialogue.

The diplomatic world appeared taken by surprise, both by the Iranian-Saudi reconciliation, as well as by China’s involvement. The sight of a Sunni Kingdom, a Shia revolutionary republic, and a Communist state cosying together was somewhat unsettling for some. Many rushed to welcome the deal, others, especially among the chattering classes in Washington, rushed to criticise it.

Diplomatic contacts have been ongoing between Tehran and Riyadh for some time, held mainly in Baghdad and Muscat with Iraqi and Omani facilitation. After the UAE normalised relations with Iran some months ago, it was assumed that sooner or later Saudi Arabia will follow. But the timing and context of the deal announced in Beijing last week remains a very significant development, with wide-ranging consequences. It also appears to herald a new age of pragmatism in international relations, with considerable implications.

A victory for pragmatism

Over the last days there have been endless commentaries about who emerged from the deal as the winner. Was it the Iranians who claimed a diplomatic victory against attempts to isolate them internationally? Or was it the Saudis who hope the deal will lead to a swift end to the Yemen civil war? Or was it perhaps the Chinese, who portrayed the deal as an example of good big power behaviour (as compared to those bad Americans stoking war in Europe)?

In fact this deal is a victory for pragmatism. The Saudis are not thrilled at doing this deal with Iran which they still see as a toxic force poisoning the whole MENA region. But they hope that by tying them into this new agreement they can somehow contain Iranian actions. In Yemen particularly, the Saudis are keen to limit, if not eliminate, Iranian influence. This, one suspects, is going to be the key testing ground for the new deal. But there are other reasons why a deal with Iran is good news for the Saudis. The Kingdom is in the middle of a process of change not seen in centuries.

Vision 2030, Mohammed bin Salman’s masterplan for the future, is a hugely ambitious blueprint. For it to succeed it requires, among other things, peace in the region. By doing a deal with Iran, Saudi Arabia is not only reducing the risk of an Iranian-Saudi confrontation, but is also indirectly restraining Israel and the possibility that it may unleash a new Gulf conflagration.

The Saudi decision to go for a deal brokered by China is also one that is based on very pragmatic considerations, rather than any ideology or grand geopolitics. The Saudis are likely to have been able to reach the same deal with Iran in the talks they were already having with them in Muscat and Baghdad. But in December 2022, during the visit of President Xi to Riyadh, the Saudis accepted the Chinese offer for mediation. Chinese involvement may irritate the Americans somehow, but has a number of benefits for Riyadh.

China is one of the few countries that has real influence and leverage on Tehran. Having the Chinese involved gives the Saudis some assurance that the Iranians will honour their part of the deal. China is also dependent on Saudi Arabia for its energy resources, so it is a country that Riyadh can deal with from a position of some strength, And of course, whilst irritating the United States was not an immediate Saudi objective, reminding Washington that the Kingdom has “other options” is very much part of the current Saudi narrative.

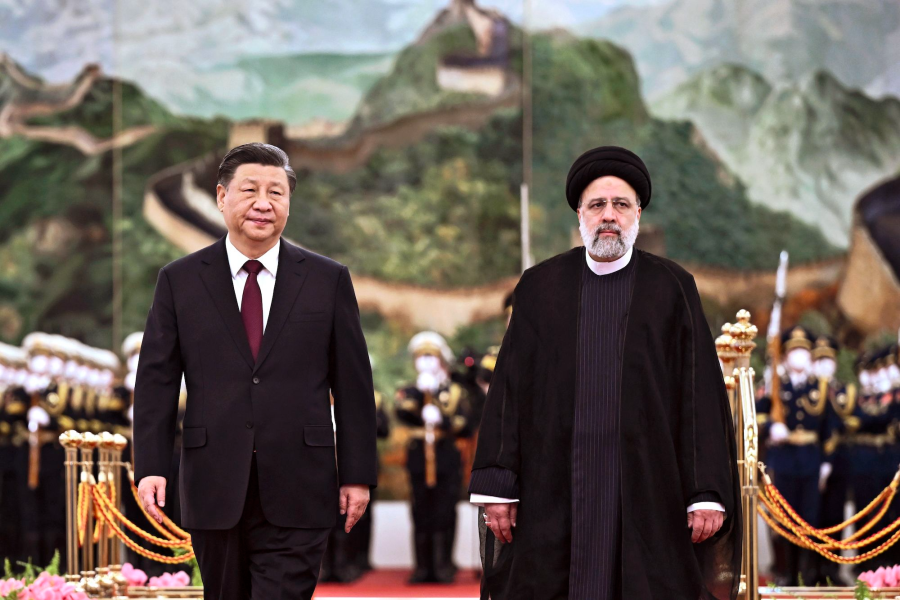

For China too, the deal is an expression of pragmatic politics. It is true that for a day or two, Beijing basked in its role as a peacemaker. China’s foreign policy chief, Wang Yi, speaking at the signing ceremony in Beijing, said “This is a victory for dialogue, a victory for peace, offering major good news at a time of much turbulence in the world. As a good-faith and reliable mediator, China has faithfully fulfilled its duties as the host.” China would continue to play a constructive role in handling issues in the world and demonstrate its responsibility as a major nation, he added.

But for China too, the reasons for indulging in this effort have been largely pragmatic. The Gulf region is now one of key strategic importance for China, providing a key source of energy supplies, and markets for Chinese products. So China had no choice but to get involved in order to lessen the possibility of further turmoil in the region, even if by brokering the deal Beijing has assumed a certain responsibility for it. If it goes wrong, and the risk is high, there will be a diplomatic price for Beijing to pay.

As for the Iranians, the leadership in Tehran is aware that the deal narrows its freedom of movement in the MENA region. To what extent is still to be seen, since many details of the Saudi-Iranian discussions are unknown. The Chinese involvement is for Tehran a double-edged sword. On the one hand it solidifies the relationship with China and adds kudos points for Iran in Beijing. On the other hand it gives the Chinese the sort of leverage that Tehran may prefer to do without. But for Iran the deal is important because it eases international pressure, and further isolates Israeli attempts to build a reasonable consensus for a military intervention against it. The deal therefore gives Tehran time, and breaks some of the current diplomatic isolation of the Islamic Republic.

What the Saudi-Iran deal does not do is to bring peace to the Gulf and wider MENA region. The Sunni-Shia rivalry, stoked for the last four decades by the clerical regime in Tehran, remains acute; there are no signs yet that the activities of the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guards – a state within a state – are being reined in; and issues such as the nuclear programme and the oppression of the Iranian people by the clerical regime in Tehran are likely to get worse before they get better. Still, overall this deal is good for the region.

The west needs to adopt a pragmatic approach too

It is important that the west adopts a pragmatic approach too, and first to the deal itself. It has been cautiously welcomed by Washington, and that is how it should be. The more countries agree to work in the framework of diplomacy and diplomatic rules, the better it is for everyone.

A more pragmatic approach is also necessary in articulating the future relationship of the west with the MENA region. Some may consider this to be cynical and unsavoury but is dictated by reality. Finding the right balance may take a while and will not be easy. The world is entering an age of pragmatism, where differences on principles and ideology make way for decisions based on expediency. The Saudi-Iranian deal brokered by China last week is a good example of such an approach. Time will tell how efficient and effective this is going to be, and its impact on world peace and prosperity.