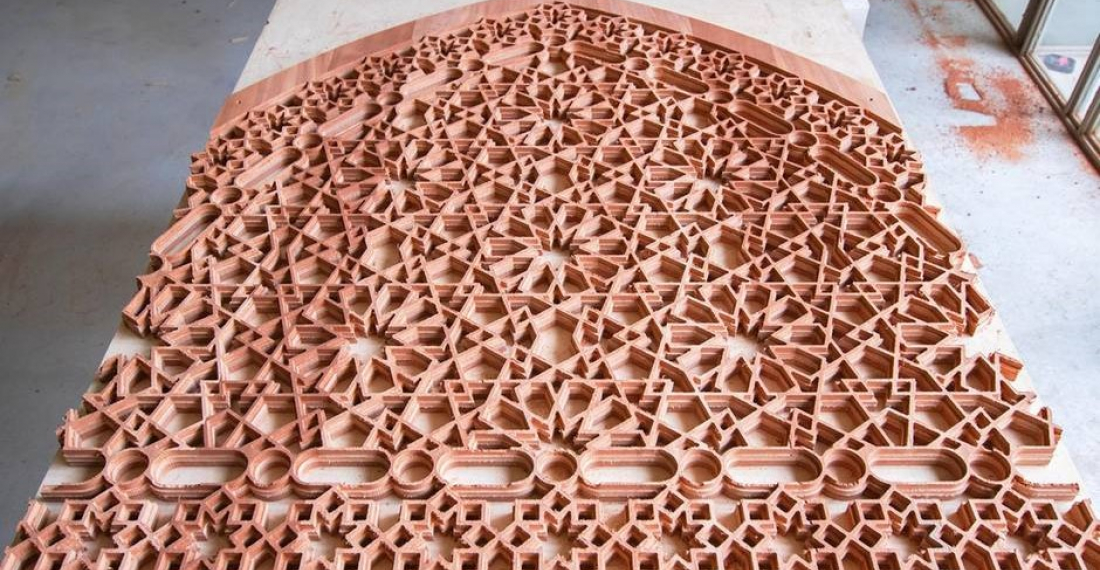

In Tripoli, Lebanon’s second-largest city, woodcarvers and carpenters are attempting to restore wooden latticework panels, known locally as 'moucharabiya'. Many of the woodwork used in traditional homes was destroyed in the Beirut port blast last August.

“The biggest challenge is trying to restore all the original details exactly as they were,” one carver says.

The work of the carvers also aims to preserve the woodwork profession. The ageless craft is part and parcel of the port culture of one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited cities. Most of the wood workshops are family-owned workshops that date back generations.

The pioneers of Tripoli's woodcarvers were from Greek or Armenian origins or from other parts of the Ottoman Empire. Many came as refugees fleeing Ottoman oppression and found home in the cosmopolitan Mediterranean city.

“They stopped at Tripoli’s port on their way to other cities, and some of them settled there,” says Vahe Okaijian, business manager of Al Mina workshop Okaijian, which focuses on architectural woodwork. His great-great grandfather came to Tripoli as a wood merchant from what is now modern-day Armenia.

The industry boomed during the French mandate when carpenters furnished the homes of the French officers. The French presence also provided a chance to learn new styles that ultimately blended with Ottoman and local influences.

Today, after the civil war, the industry stands on its last legs but luckily a local NGO has been connecting the city’s carpenters with Lebanese designers. Carvers learn from old photographs and use a digital woodwork machine to recreate patterns.

Workshops are also held to maintain the craft and the workers are looking for potential markets in the GCC and Europe to sell their products.

Source: commonspace.eu with The National (Abu Dhabi).

Picture: Sample of the woodwork carved in Tripoli, Lebanon.