It is now 31 years since I first travelled from London to the South Caucasus to report from what was then Nagorno Karabakh. Since then, I’ve covered almost every dimension of the conflict. From the Azerbaijani POWs and civilian hostages I encountered on my first trip to Karabakh in 1994, through the ethnic Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan struggling to rebuild their lives in Armenia that same year and then from 1999, and the lingering danger of landmines and unexploded ordnance that plagued the seven formerly occupied regions of Azerbaijan surrounding Karabakh throughout the 2000s. They still claim lives today.

From conversations with Zori Balayan and meeting with Seta Melkonyan in 1994 before interviewing her in 1999, and in the here and now, from Benyamin Poghosyan and Mikayel Zolyan last year, it is important to speak to everyone. From former Lebanese Armenian commander Jirair Sefilyan in the late 2000s to the National Democratic Pole’s Vahe Gasparyan last year, and recent refugees from Karabakh when I visited in 2024, it is vital that everyone is heard. And from all sides.

From Farid Shafiyev to Vasif Huseynov, and from Boris Navasardian to Hrant Mikaelyan, even if you can’t meet them in person, there is always Tbilisi and YouTube. There is also what many others write and publish online.

Times have changed, of course. Border communities in both counties will increasingly find themselves in close proximity to each other again and the long and difficult process of reconciliation, where direct communication is essential, must finally begin. It was really only individuals such as the late Georgi Vanyan and some others that attempted to bring actual people, including from districts such as Noyemberyan and Qazakh, together. I was fortunate to document some of that work. Sadly, others in Armenian civil society and allegedly the security services of all countries involved opposed it.

From 2008 onwards, I did at least harness new and social media tools to connect young Armenians and Azerbaijanis online, the only way to do so across the closed border. None of that was sufficient, however. Online, people tend to immerse themselves in echo chambers, something that is clearly evident today. The same is true when it comes to consuming media in general. From 2009 until today, my personal work focused instead on alternative and counter-narratives – including from where the two peoples already live together in mixed villages and towns.

Some welcomed this, especially in Azerbaijan, and even including now presidential advisor Hikmet Hajiyev. Sadly, and like Vanyan before me, even 15 years ago in Armenia, where many believed they would remain victorious, such ideas were met with hostility and derision. Accepting it would be tantamount to admitting Karabakh would never be independent or that territory captured in the early 1990s would have to be returned. The reality, however unpalatable to some, is that the political entity's future was always tied to its gradual integration within Azerbaijan because of geography. Those were activists, of course. Others were different.

I remember on one of my many visits to Lachin in the early 2000s that the Armenian family from Yerevan, eking out a shockingly desperate living in the remnants of what had been the home of an Azerbaijani family just years before, kept an old photograph of its former inhabitants. “They looked like normal people,” they sadly said. It was a momentary moment of empathy that offered some hope.

Further pain has been experienced since, especially in September 2023 with the exodus of 100,000 ethnic Armenians from Karabakh. Nonetheless, and for the first time in recent history, last week’s meeting between Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev, and US President Donald Trump at the White House, offered another glimpse of hope. It felt as if normalising relations could be on the horizon this time. Criticism of Trump’s role in this process is of course valid. The summit did seem more about his own insatiable quest for a Noble Peace Prize than the wellbeing of those that have suffered to date.

Nonetheless, earlier this year in Bagratashen, an Armenian village just across the border from the ethnic Azerbaijani village of Sadakhlo in neighbouring Georgia, residents told me they believed peace would only come if the American or Russian presidents wanted it. Like it or not, Trump’s involvement could sway such a demographic. Assuming, of course, the U.S. remains true to the task at hand.

There is of course much to critique of both the summit and the declaration, but now is not the time. Criticism is easy before actual details and informed discussion emerge. That has always been the case in this conflict. Today it might be even more so given parliamentary elections scheduled for Armenia next year and a flood of local and foreign misinformation, disinformation, and propaganda that will emerge. Time has never been on the side of an Armenia-Azerbaijan peace agreement.

This is the time to support, not obstruct, such an opportunity. There will be challenges, but those can be addressed if there is genuine political will and open discussion rather than incessant argument. There do remain legitimate concerns to address, but they must be approached constructively and not with the intention of derailing the peace process for personal, ideological, or geopolitical ambitions. Moreover, the opinions of the citizenry must be heard too. They should no longer be excluded, marginalised, or even silenced.

This was the mistake the opposition and some foreign commentators and civil society actors have made over the past three decades. Nobody says it will be easy, but if there is the opportunity to end this conflict then it must be seized. There is little point in opposing peace if there is nothing realisable to offer in its stead. Iran’s concerns must somehow be addressed, true, and it would be better for Armenia to maintain healthy relations with Russia, highlighting another important issue. It would be better that geopolitical rivalry doesn't first tear the region apart. The potential consequences of that are unthinkable.

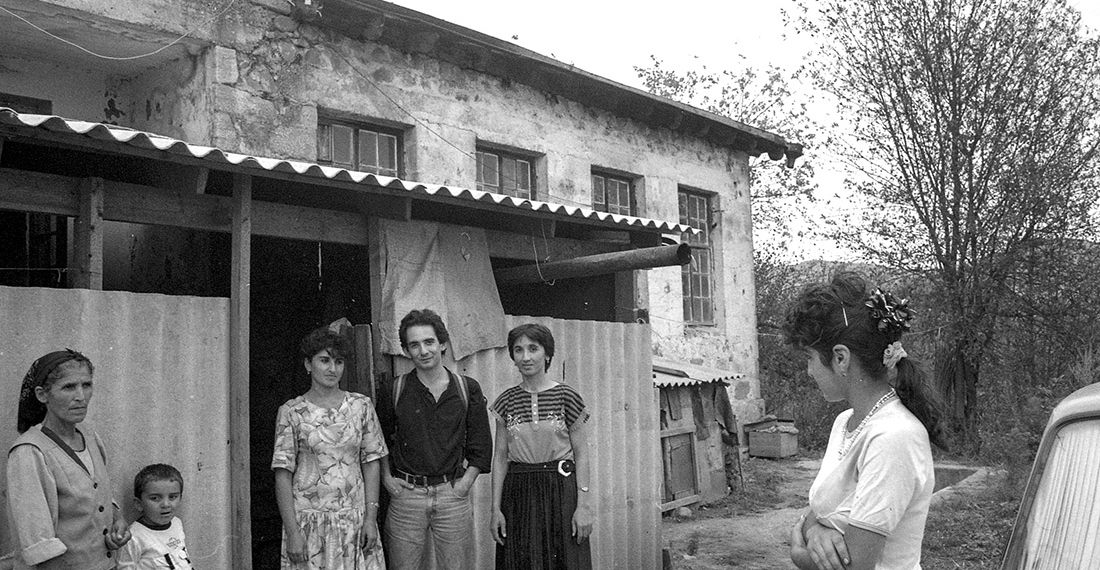

source: Onnik James Krikorian is a journalist, photojournalist, and consultant from the U.K. who has covered the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict since 1994. Photo: Onnik James Krikorian in Khramort, Nagorno Karabakh 1994

The views expressed in opinion pieces and commentaries do not necessarily reflect the position of commonspace.eu or its partners.