The shift in the regional balance of power after Azerbaijan’s victory over Armenia in the Second Karabakh War and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine have led to remarkable changes in Azerbaijan’s and Iran’s threat perception about each other, fueling a security dilemma spiral, writes Mahammad Mammadov for commonspace.eu.

In a break with the past, serious concerns about potential security challenges emanating from the other side have been rising in Baku and Tehran. While Azerbaijan views Iran’s support for proxy groups inside the country as a threat to its national security and perceives the deepening Iran-Armenia partnership as detrimental to its regional standing, Iran has been concerned with Azerbaijan’s growing military potential in partnership with its arch rivals - Israel, Türkiye, and the West - as being deleterious to its strategic interests in the wider neighbourhood.

Over the past few months, Iran has been using a combination of hard and soft power tools to tame Azerbaijan’s confident external posture and prevent it from getting closer to Israel. Tried with mixed results toward some of the Gulf countries, this strategy mostly backfired in the case of Azerbaijan. In 2022, Azerbaijani security services arrested tens of pro-Iranian Shia figures to neutralise Tehran’s alleged attempts to destabilise the country from within. To deter Iran’s military buildup near its borders, Azerbaijan conducted joint military exercises with Türkiye along its borders with Iran and increased the scope of its politico-military cooperation with Israel. In January 2023, Azerbaijan closed its embassy in Tehran after a terrorist attack that killed the security chief and wounded two other guards. To Iran's mounting ire, Baku opened its embassy in Israel in March with the attendance of the two countries’ foreign ministers, and expelled several Iranian diplomats working in Baku as persona non-grata shortly afterwards.

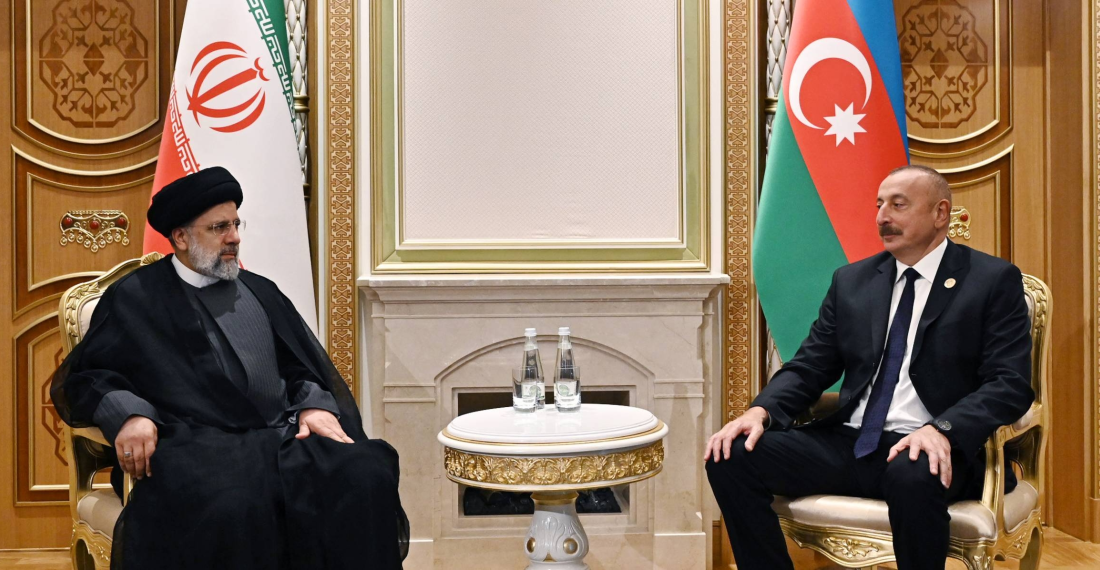

To calm the waters, Tehran recently toned down its aggressive rhetoric towards Azerbaijan, signaling readiness to resolve problems through dialogue and negotiations. Among others, the Iranian side appealed to Azerbaijan to restore the work of its diplomatic mission in Tehran but Baku conditioned this to the proper punishment of perpetrators and instigators of the terrorist attack by Iranian authorities. After a flurry of phone calls between the foreign ministers during the last two months, Iran’s Foreign Minister Amir Abdollahian visited Baku on 5 July to participate in the Non-Aligned Movement ministerial meeting where he reiterated Iran’s firm commitment to resolving mutual misunderstandings with Azerbaijan.

For Azerbaijan, good neighbourly relations with Iran means it can consolidate its focus on ongoing peace talks with Armenia and more immediate challenges emanating from the Russia-Armenia partnership

Easier said than done, putting relations on pragmatic rails could help both countries make better use of strategic opportunities offered by new geopolitical realities in the region conditioned by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. With Moscow’s turn to alternative markets to compensate for its economic isolation from the West, Azerbaijan and Iran emerged as pivotal players for intercontinental north-south transport routes linking Russia to India. Growing connectivity links could not only bring economic dividends in terms of transit fees and integration into regional supply and value chains but also create mutual economic interdependencies capable of throwing sand in the gears of widening cracks in Azerbaijan-Iran ties.

In May, Russia and Iran signed an agreement on the completion of the Rasht-Astara railroad that will link Iranian and Azerbaijani railroad systems with positive implications for mutual trade which grew 8% in the first half of 2023, compared to the same period of the previous year. After his meeting with President Ilham Aliyev on 5 July, Abdollahian said the two sides had also agreed on activating the South Araz corridor that would connect Azerbaijan’s Eastern Zangezur economic region with Nakhchivan through the Iranian territory, bolstering communication links between the two countries. Last but not the least, Baku and Tehran cooperate on a three-way gas swap deal envisioning the transit of the Turkmen gas to Azerbaijan that will see Iran expand its gas transit capacity and help Azerbaijan meet its growing domestic demand and export commitments to European customers.

The remarkable detail about the recent thaw in the Azerbaijan-Iran relations is that it comes on the heels of a shifting geopolitical landscape in the Middle East, marked by increasing multipolarity with serious implications for the Raisi government’s neighbourhood policy. Normalisation of relations with Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, and potentially with Bahrain and Egypt could be a boon for Tehran’s regional posture, expected to alleviate the theocratic regime’s headaches regarding economic hardships, external support for opposition groups inside the country and potential risks associated with power succession in Tehran after the eventual death of Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. This external opening is believed to widen Iran’s room for manoeuvre in the neighbourhood, strengthening its hand vis-a-vis Israel and the U.S. in regional affairs. For Azerbaijan, good neighbourly relations with Iran means it can consolidate its focus on ongoing peace talks with Armenia and more immediate challenges emanating from the Russia-Armenia partnership.

Tehran and Baku have so far failed to build a durable partnership mechanism that could help deal with uncertainty and mistrust in the bilateral relations

Whether this normalisation drive will have a sustainable positive impact on Azerbaijan-Iran relations is questionable at best as it does little to remove key structural barriers to friendly relations. First of all, the Raisi administration’s approach to normal ties with neighbouring countries has so far been mostly situative, aiming to serve Iran’s interests at the expense of others rather than creating sustainable multilateral frameworks to institutionalise international cooperation. Tehran and Baku have so far failed to build a durable partnership mechanism that could help deal with uncertainty and mistrust in bilateral relations. Growing economic cooperation could be an essential component of friendly ties but if the recent past is a guide, it hardly deters escalations when geostrategic interests are at stake.

Secondly, the consolidation of power in the hands of hardliners in Iran does not bode well for its ties with Baku. The growing role of IRGC cadres in Iranian foreign policy may keep the spotlight on ideological differences and widen the scope of securitization in bilateral relations.

Thirdly, Azerbaijan shows no interest in bowing to Iranian pressure to limit its partnership with Israel and instead doubles down on expanding ties in different spheres. If the Gulf countries chose to engage Iran mainly due to the U.S. failure as a security guarantor in the region, Azerbaijan sees in Israel a reliable partner for neutralising regional challenges. Similarly, Iran - together with France and India - emerges as a crucial partner for Armenia in balancing Azerbaijan's ambitions as Yerevan now sees Russia as an unreliable ally.

Lastly, Iran's view of Azerbaijan as a “normal” country shows no signs of change under current circumstances. As Putin's Russia views “normal” Ukraine as a country mostly aligning its foreign policy interests with Russia, Iran expects “normal” Azerbaijan to avoid partnerships challenging Iran's regional interests, thus depriving it of its agency in alliance-making. It is in this context that Iranian leaders frequently claim that Azerbaijan's interests are Iran's interests.

After the Iranian Foreign Minister’s recent visit to Baku, Tehran Times, a news outlet linked to Ayatollah’s office, ran an article titled “Another chance for Baku”, alluding to Iran’s patience with regard to Azerbaijani partnership with Israel and the West. Baku seems to be adamant in its willingness to continue pursuing an independent foreign policy regardless of Iranian pressures and it will certainly put the two countries in a dangerous spiral despite their vast potential for partnership and neighbourly relations.