The dust of war from the decades-long conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan has started to settle, and although peace remains elusive, there is hope across the region for a better future. No-one has waited for this moment more than the hundreds of thousands of Azerbaijanis who were displaced by the First Karabakh War in the early 1990s.

Landmines are the biggest obstacle for the right of IDPs to return

The right of internally displaced persons (IDPs) to return voluntarily to their homes in safe and dignified conditions, once a conflict has ended, is enshrined in customary international humanitarian law and practice. After the Second Karabakh War ended in November 2020, Azerbaijani IDPs waited expectantly for the return. One thing has stood in their way since: the hundreds of thousands of landmines and explosive remnants of war that infest the territories from where the IDPs originated.

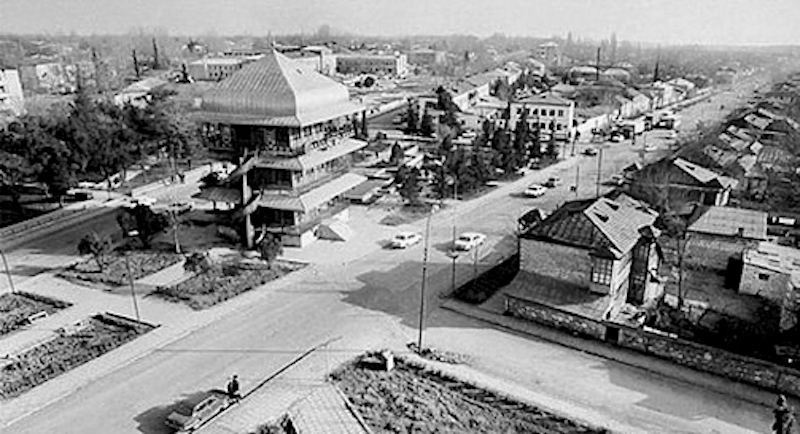

One of these territories is Aghdam. According to the last Soviet census in 1989, Aghdam had a population of 131,293, of whom 28,000 lived in the town of Aghdam and over 103,000 in surrounding villages and other rural settlements.

On 23 July 1993, during the First Karabakh War, Armenians took control of Aghdam, causing the population to flee to other regions within Azerbaijan. Many of those who fled thought they were going away for a few days. Thirty years later, they are still waiting to return.

During the time of Armenian control, Aghdam was virtually abandoned, with no significant Armenian population settling in, apart from a military presence and occasional looting raids on the ruins of the houses that were stripped of everything - windows, wood, tiles and more, leaving behind a disturbing skeleton of a town - essentially rubble, save for the twin minarets of the main mosque. For 27 years, the situation remained stagnant. The ruins crumbled, while shrubs and trees took root in the remains of the walls, softening the harshness of the scene.

According to the trilateral agreement of 10 November 2020 between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Russia that ended the Second Karabakh War, it was decided that Armenian forces would withdraw from the city. Azerbaijani troops began moving into the city on 19 November 2020, and by 20 November 2020, both the city and its surrounding territory had returned to Azerbaijani control.

Many IDPs were elated, and some tried to move back to the town within days. Very soon, however, reality struck. It was not only that the city and district were just a mound of rubble, it was also that even to reach it was hazardous if not impossible due to the large-scale infestation of landmines and other explosive remnants of war. Return had to wait until the area was cleared of landmines, and that was likely to take considerable time.

Shocking scenes that remind of Hiroshima

On 25 May, I travelled with other members of the international community to the town and district of Aghdam in the framework of a United Nations Conference “Mine Action: The Path to Reaching Sustainable Development Goals”. The conference was organised by the UN together with the Azerbaijani State Demining Agency, ANAMA.

We approached Aghdam by bus, and crossed the former line of contact, marked by the so-called “Ohanian Fence”. We drove past village after village, settlement after settlement, all reduced to sheer rubble, until we hit the town itself, which again was simply piles of rubble with not a single building standing, except for the minarets of the mosque that were preserved to be used as watchtowers. Many remarked that the scenes reminded them of pictures of Hiroshima after the nuclear bomb fell on it.

The tragedy is that landmines now are slowing down, if not outright preventing, reconstruction. Our group observed deminers from ANAMA at work, patiently working their way meter by meter, at great personal risk, to clear the area. It is painfully slow work. The road to the restoration of Aghdam is undeniably long. Along the former line of contact, there are not only landmines and UXOs, but also booby traps where the chances of human survival, if triggered, are almost non-existent. This predicament adds an extra layer of complexity to the region's problems.

The process of demining goes on in earnest but takes time

Although progress has been made in demining Aghdam, resource and time constraints limit the pace of clearance. As of May 2023, approximately 30% of the suspected hazardous area in Aghdam has been cleared. This has enabled the government of Azerbaijan to start the reconstruction process. The government is under pressure from the IDPs who want to return as soon as possible. In the areas already cleared of landmines the government is laying the necessary infrastructure, building communal buildings such as schools and hospitals, as well as housing complexes for internally displaced persons (IDPs). Some criticism has arisen because the original residents, who were used to traditional houses with gardens, are now being allocated apartments in multiple-storey buildings. Nevertheless, the urge to return home is strong among the residents. They are eager to see the transformation of Aghdam once the reconstruction process is complete.

The city's reconstruction plan is ambitious, and takes into account that the IDPs returning now also bring the families they have raised in the last thirty years since displacement. The city’s master plan now includes the amalgamation of eight neighbouring villages into Aghdam town, bringing the new urban area to an estimated population of around 100,000. Housing is expected to consist of multi-storey buildings and private residences. Designed as a 'smart city', Aghdam will be surrounded by gardens, positioning it as a green energy hub. Within the city limits, there are ambitious plans for a sprawling green zone covering 125 hectares. An artificial lake, canals and bridges, highways, pedestrian and cycle paths, and electric public transport are integral parts of the city's blueprint.

How fast that this be achieved depends mainly on how quickly deminers from ANAMA and other demining agencies can work. To understand the scale of the problem, to give an example, on a stretch of land two kilometres long it is estimated that more than 50,000 anti-tank and anti-personnel mines are dispersed. This area encompasses seven villages from Aghdam District, which were previously located on the former line of conflict.

Despite clearance efforts, there have been several tragic incidents. Since November 2020, ANAMA has reported more than 20 accidents involving mines in Aghdam, causing deaths and severe injuries. In general, since the beginning of the first military conflict, some 3,400 citizens of Azerbaijan have been injured by landmines, and 587 of them have lost their lives. It has also been revealed that some 302 Azerbaijani citizens have been affected by landmines in Azerbaijan in the last 32 months. ANAMA reports that mine explosions have caused 57 deaths and 245 injuries among the population.

Aghdam is a mute witness to the cost of conflict

Aghdam stands as a mute witness to the cost of conflict. But it is also a testament to the indomitable human spirit and humanity’s capacity for resilience and transformation.

The problem of landmines in Azerbaijan is huge. Most of it is the result of the long conflict with Armenia, but some of the problem dates back from Soviet times. The Soviet 4th Army was based in Azerbaijan and it protected all its bases with a ring of landmines around them. Landmines were also used to defend border areas. However, Azerbaijan does not have a monopoly of the landmine problem in the South Caucasus. Armenia and Georgia have landmine problems too, even if they are on a much smaller scale. Clearing the region of landmines is essential for future development and to consolidate peace. The countries of the region need international support to achieve this goal.

It takes only a single euro to produce a landmine, but it takes a thousand to find and dismantle it. But this should not deter us, it should motivate us. Just as every euro invested in the creation of a landmine can cause harm, every thousand euros spent on its removal can bring peace and hope. We should not shy away from this cost, for in the mathematics of peace, the value of a life, a smile, a safe step, is priceless. Every landmine cleared is a step towards a safer world; a healed Aghdam, can be a testament to the power of peace. Our fight against landmines is not just a fight for the physical reclamation of land, but for the very essence of humanity, for the certainty that every child can walk around his village without fear, every seed can grow unthreatened, and every city can thrive free from the scars of the past.