As the global order continues to morph into a more complex architecture with an array of global and regional powers, the geopolitical future of the South Caucasus hangs in the balance. The tectonic changes in the region of the last four years – the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, the regional implications of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the military takeover of Nagorno-Karabakh by Azerbaijan, and forced displacement of Armenians, the EU candidate status for Georgia and Georgia’s quest for multi-vector foreign policy including the establishment of strategic partnership with China, the limbo in Armenia–Azerbaijan negotiations, growing assertiveness of Azerbaijan and eventual move of Armenia towards closer cooperation with the EU and the US – all make the situation quite complex.

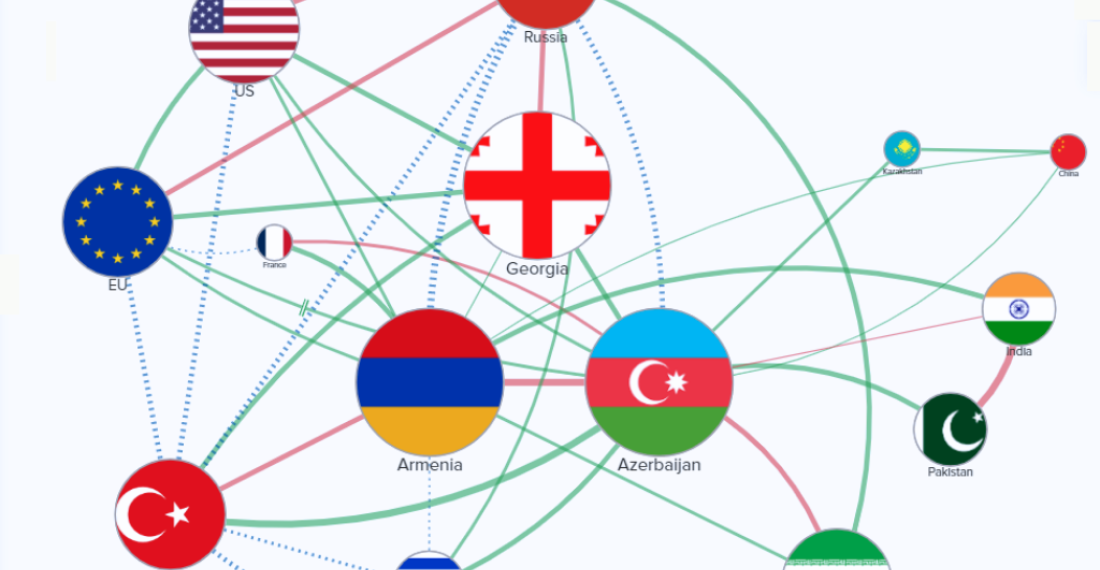

Some argue that the South Caucasus is the microcosm of the current confusing global power architecture, with conflicting, competing, and coinciding interests of an array of regional and global players, such as Russia, Iran, Turkey, the US, Israel, the UK, India, Pakistan, China, the EU, and individual EU members. The most short-term threat to regional security is a possible new escalation by Azerbaijan against Armenia, which could result in the involvement of other actors, igniting a regional war with the direct participation of Iran, Turkey, and Russia, and the indirect involvement of Israel and Pakistan, India, and France. If it becomes a reality, this will have severe implications for all regional states and all powers interested in a stable South Caucasus crossroad region. Everything should be done to dissuade Azerbaijan from the new use of force against Armenia and return to meaningful negotiations in good faith.

In the longer run, the key question is the geopolitical future of the South Caucasus in a post-unipolar world. Two potential pathways of future development present themselves to the region. In the first scenario, the region becomes an active battlefield of different regional and global actors and may end up being fragmented and divided. In this case, the borders between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia may become the new fault lines between the new poles of the regional and world order, which will prevent regional cooperation and negatively impact the chances for regional stability and prosperity and turn the region into a trade and transport hub.

If Georgia and Armenia end up being part of the West and Azerbaijan moves closer to the Turkic world while keeping a balance with Russia and Iran, then the Armenia - Iran border will become a fault line between the West and Russia – Iran axis, while Armenia – Azerbaijan and Georgia – Azerbaijan borders will be a line between Western and non-Western worlds. If Georgia joins the West, while Armenia remains within the Russian sphere of influence, the Armenia – Georgia border will become a new fault line between Russia and the West.

Some may argue that the best solution would be to include the entire South Caucasus into one pole of the emerging new world order, thus unifying a region and preventing the establishment of any dividing lines. However, this scenario is quite unrealistic. Even if Armenia and Georgia join the West, which itself seems quite challenging as Russia and Iran probably will do everything to prevent such a scenario, Azerbaijan has no intention of joining the West. If Armenia remains under the Russian sphere of influence, it is hard to imagine Georgia joining the Eurasian Economic Union or any other Russia-led organization. Georgian society has a clear pro–European and anti-Russian stance, and there is no realistic way to change the situation significantly from a short- or mid-term perspective. Even if Russia decides to repeal its recognition of Abkhazian and South Ossetian independence, a process which itself seems quite unlikely, pushing forward the idea to transform Georgia into a confederation or federation with Abkhazia and South Ossetia, this will not guarantee Georgia's u-turn in foreign and defense policy towards Russia. Meanwhile, as Azerbaijan puts more emphasis on its foreign policy on the development of cooperation with Turkic states, it is challenging to imagine Azerbaijan joining the EU, Eurasian Economic Union, or CSTO.

Another negative impact of the first scenario will be the fact that the countries of the region will have little, if any, say on regional developments, will lose their agency and capacity to influence the issues directly related to their fate, and will be forced to follow the line of their regional or global patrons.

However, there is an alternative future for the South Caucasus to avoid being a fragmented region under the influence of competing powers. In this future, the region will become a bridge for regional and global actors, fully realizing its potential to serve as a transit and logistic hub for Europe, Russia, the Middle East, India, and China. In this scenario, the region will not be part (fully or partly) of any emerging geopolitical and geoeconomic power in the post-unipolar world. This scenario will transform the region not only into a transit and logistic hub but also a convenient platform for global and regional players' track 1, track 1.5, and track 2 dialogues, including US – Russia, US – Iran, the EU – Russia, and others.

This scenario will increase the agency of regional states, and they will have the capacity and capability to impact the developments in the South Caucasus and have a say about their own future. The mandatory condition for the realization of the second scenario is the launch of dialogue and cooperation between all three states of the region, and as the first step towards this direction, countries should accept and adhere to the international law, including non-use of force, respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty of each other. After more than 30 years of conflicts and wars, this scenario may seem unrealistic. However, this is the only option to provide a secure, stable, and prosperous future for the region and its people. The first step towards the realization of this scenario could be the launch of regional expert platforms for discussions and debates using the toolkit of Track 1.5 and Track 2 diplomacy. Then, ideas and suggestions elaborated and agreed on in those platforms can be delivered to the relevant officials in the region and beyond, including Russia, Iran, Turkey, the EU, and the US.

Benyamin Poghosyan is a Senior Fellow on foreign policy at APRI Armenia and the founder and Chairman of the Centre for Political and Economic Strategic Studies in Yerevan.

The views expressed in opinion pieces and commentaries do not necessarily reflect the position of commonspace.eu or its partners.