This editorial first appeared in the 15 June 2023 issue of our newsletter, Caucasus Concise. If you would like to subscribe to Caucasus Concise, on any other of our newsletters, please click here.

"These are difficult times for Georgia, for Europe, and for the whole world. Yet from every crisis, an opportunity arises. The Ukraine crisis has created conditions that open Georgia’s door for EU membership. Regardless of the rather unorthodox path this endeavour has taken, future generations of both Georgians and Europeans will look back at this historic moment, and say that the right thing was done," writes commonspace.eu in this editorial. "But before that, there is much work to be done. Candidate status will only be the beginning of a long, laborious and difficult process. And as a priority, the EU needs to develop a much more sophisticated communication strategy for dealing with Georgia and the Georgian people."

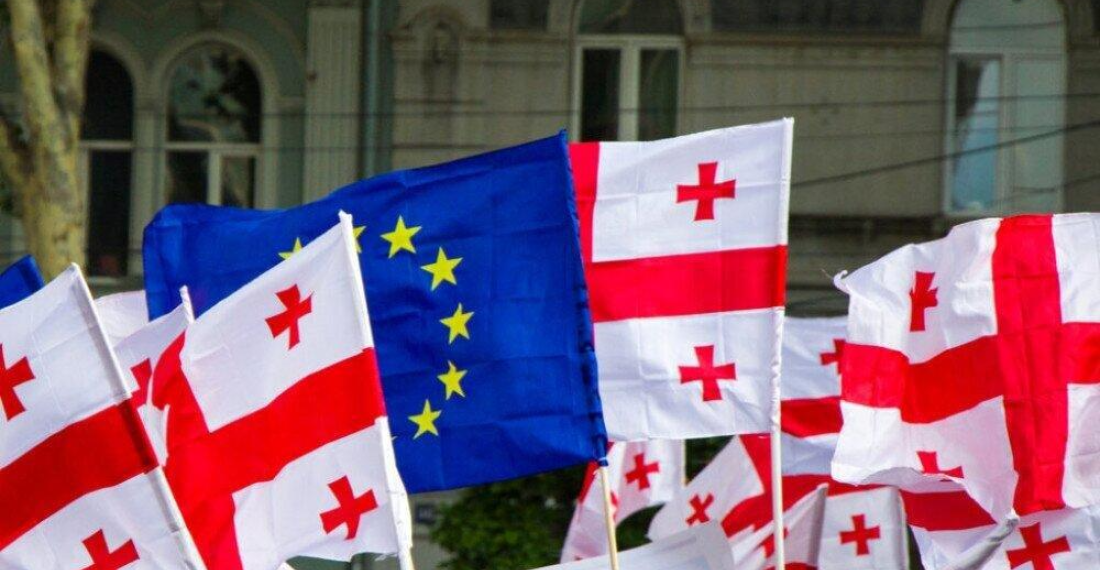

That the vast majority of the Georgian people want to see their country anchored in Europe is a certainty, even if their idea of what Europe is, is somehow blurred and outdated. That it is also in the interest of the European Union to have Georgia as close to it as possible for political, economic, strategic, cultural and social reasons, is equally certain. Everything else connected with Georgia’s current bid to secure candidate status in the EU by the end of the year is subject to many interpretations and nuances. This notwithstanding, it has now become amply clear that, despite whatever subjective reservations there may be, giving Georgia EU candidate status is now necessary.

Events have forced the issue. Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, left the European Union with no choice but to revisit with urgency the desire of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia for EU membership. Only a few months before the invasion, on the eve of the Eastern Partnership summit in December 2021, the only thing that was being actively discussed was whether or not to give the three countries “a membership perspective” – a very loose indication of intent. At the time the three countries would have been content with that, for a while at least. Three months and a Russian invasion later, the situation was completely changed. Beleaguered Ukraine needed to be reassured; the fate of Moldova and Georgia was already somehow attached to the Ukrainian bid.

In June 2022, the European Commission, in its wisdom, decided to give Ukraine and Moldova candidate status, and separated Georgia from the process, instead giving it the feeble “membership perspective”. The Georgians were given a “to do list” of 12 points, which they had to implement before the candidate status could be considered. The Georgian government now claims that it has fulfilled all the requests, and that now the EU must keep its word and extend the candidate status.

Anchoring Georgia in Europe is the only way forward from both the Georgian, and the European perspectives

That at least is the formal part of the story. This piece of European bureaucratic endeavour has played out with the Ukraine-Russia war in the background, and a permanent state of political crisis in Georgia as the Georgian Dream government fended off weak, but persistent attacks from the opposition, more effective but somewhat erratic efforts of civil society, and sniping from the side from the Georgian president who has made no secret of her displeasure with the current state of play.

In such a scenario, the European Commission would normally be reluctant to extend candidate status, and would have cited this as one reason why not to. But there is nothing normal about the present time. Anchoring Georgia in Europe is the only way forward from both the Georgian, and the European perspectives. Getting candidate status appears to be the only thing Georgian politicians seem able to agree on these days. That has narrowed the options for the European Commission. But even more interestingly, European governments, including some of those who were adamant they did not want another wave of EU expansion anytime soon quickly changed their mind once Russian tanks were outside Kyiv. On Georgia, too, a more strategic approach is now at play.

The European institutions must therefore adopt a strategy that is fit for the current situation. Firstly, this should include that between now and December the Commission needs to squeeze out every concession it can from the Georgian government, in line with the 12 point list, especially when it comes to justice and the rule of law. Second, it must grant Georgia candidate status no later than the end of this year. And third, candidate status can be accompanied by a strategic agreement covering relations in foreign policy and security. This would be unprecedented, and the legal status of such an agreement would be hotly debated, but such a step has become necessary due to the very ambiguous statements made by the Georgian government in the aftermath of the launch of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. Much harm has been done to those relations by those statements – and some insist that they were meant to do just that. In any case a candidate country would be expected to behave differently, and this needs to be agreed upfront.

There is much work to be done as Georgia moves towards the EU

These are difficult times for Georgia, for Europe, and for the whole world. Yet from every crisis, an opportunity arises. The Ukraine crisis has created conditions that open Georgia’s door for EU membership. Regardless of the rather unorthodox path this endeavour has taken, future generations of both Georgians and Europeans will look back at this historic moment, and say that the right thing was done.

But before that, there is much work to be done. Candidate status will only be the beginning of a long, laborious and difficult process. And as a priority, the EU needs to develop a much more sophisticated communication strategy for dealing with Georgia and the Georgian people. Its useless preaching values or stating hard truths unless you can explain them in the way that your audience can understand them. Those that wanted to drive a wedge between Georgia and the EU have played on this weakness. If Georgia becomes a candidate country, dealing with this issue will become easier to deliver, even if achieving the objective will still be difficult.