With parliamentary elections in Armenia just over a year away, opposition figures and some analysts are increasingly questioning Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan’s prospects for re-election. Critics argue that he has failed to fulfil his widely promoted peace agenda and hold him accountable for the exodus of approximately 100,000 ethnic Armenians from the former Soviet-era Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast (NKAO) in late September 2023. They also point to unrealistic campaign promises made during the last parliamentary elections held in 2021, including the pledge to reclaim the strategic hilltop citadel of Shusha and pursue remedial secession for the separatist but now dissolved Karabakh — goals widely seen as unattainable from the outset.

Some argue that it was Prime Minister Pashinyan’s refusal to acknowledge the reciprocal nature of two agreed transport linkages —from Armenia to Karabakh and Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan— in November 2020 that led to a stalemate over the Lachin corridor. This, they contend, ultimately resulted in the demise of Karabakh as an ethnic Armenian political entity and was predictable since the ink dried on the trilateral ceasefire statement. Pashinyan was to exploit the complete loss of Karabakh to pivot politically, declaring it time to focus solely on securing the future of the Republic of Armenia within its internationally recognised borders. The Armenian opposition, however, claimed this outcome was orchestrated with the backing of the European Union and United States, aimed at reducing or eliminating Russian influence in the strategically important South Caucasus.

Although the resurgence of a more assertive opposition under the guidance of Kocharyan and Sargsyan was predictable, what was less expected was Pashinyan’s ability to survive repeated political crisis after crisis. This resilience was most apparent in 2024 when Archbishop Bagrat Galstanyan, a revanchist cleric, failed to mobilise sufficient numbers on the streets to leverage sufficient public outrage just as the parliamentary opposition couldn’t even in 2022 when a pregnant woman was killed by Pashinyan’s speeding convoy in central Yerevan. On the other hand, with the trauma of defeat still fresh, many Armenians are naturally reluctant to risk further bloodshed in a conflict they are again unlikely to win. Armenia lacks meaningful security guarantees, and the European Union Mission in Armenia (EUMA) was never intended to act as one.

Nonetheless, EUMA has managed to provide a limited sense of security on the Armenia-Azerbaijan border as has a nascent process of border delimitation and demarcation. Pashinyan’s concept of a Real Armenia will likely resonate positively among those Armenians that can still remember the period 1998–2018 under Pashinyan’s predecessors as one of extreme corruption and human rights abuses. There does now exist the potential to open a new more encouraging chapter in the history of the post-Soviet Armenian republic and the entire South Caucasus region. Even so, the closer the election draws comes, the more uncertain the outcome appears. Last month’s municipal vote in the country’s second largest city of Gyumri was confirmation of that.

Although Pashinyan’s candidate for mayor attracted the largest number of votes out of any of the political forces participating, it was insufficient to install him as mayor. Instead, a highly controversial city leader of old took the position instead. Though there remains significant bad blood between that candidate and his competitors, the opposition put aside their differences simply to prevent a victory for Pashinyan’s Civil Contract. The same situation almost emerged in Yerevan’s municipal election in 2023. If such a situation was to occur in 2026 for the parliamentary vote, and though it is possible that Pashinyan could still gather the largest number of MPs, it is quite possible that they would remain insufficient to form a stable majority. A new pro-European Union alliance of Pashinyan-linked extra parliamentary forces have also been unable to appeal to an electorate desperately hoping for a third force to appear on the ballot without direct linkages to the current and previous regimes.

In Pashinyan’s favour, however, is that the opposition remains divided and discredited. No matter opinion on any peace deal hammered out by Aliyev and Pashinyan, it is the only one on the table and the opposition appears more concerned with coming to power no matter the cost and on a hardline ticket that would keep Armenia semi-isolated in the region and could provoke renewed fighting at worst. Baku has warned many times what would be its response if revanchist voices in Armenia fanned the flames of conflict. Sadly, they continue to do so on a daily basis. Some nationalist inclined analysts and civil society actors do so too.

It also seems possible that significant domestic instability is on the horizon. Street protests intended to force Pashinyan out of power now appear to be the modus operandi of choice in order to do so. None appear to understand that the only sustainable path forward lies in securing a lasting peace agreement and pursuing effective regional integration, including with neighbouring Türkiye. However, this strategy demands genuine diversification—broadening partnerships without radically shifting Armenia’s geopolitical orientation. As a small, economically fragile and landlocked country now lacking sufficient allies or any security guarantor at all, Armenia’s priority must now be to make this path both clear and irreversible.

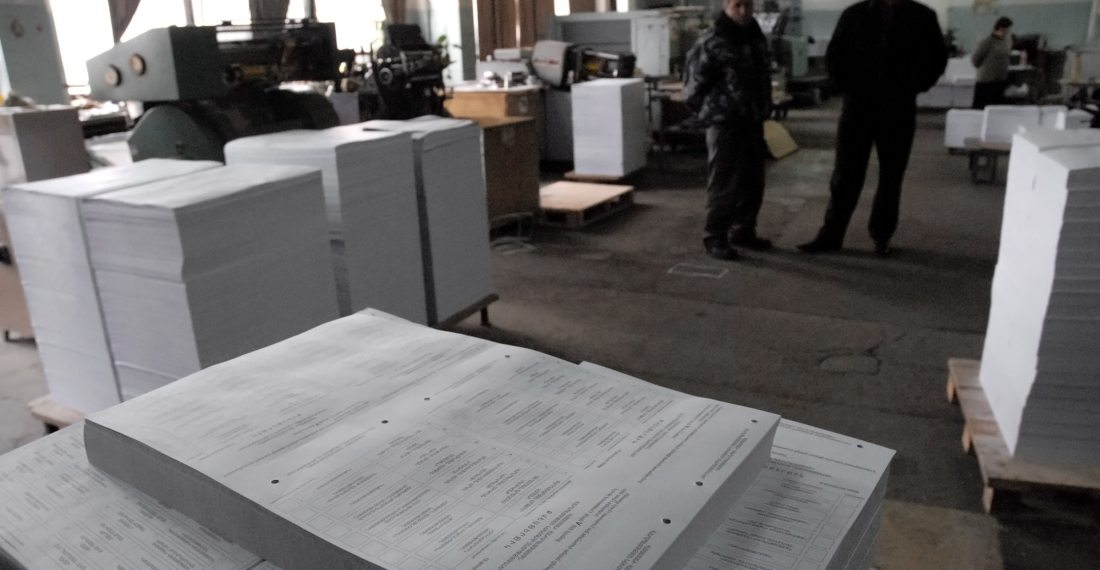

Ultimately, however, it will all depend on the electorate which will likely be overwhelmed by a deluge of partisan propaganda, misinformation, and disinformation from multiple sources over the coming year in what could prove a highly contentious and bitter period defined by geopolitical and not domestic concerns. It is high time that society engages in informed discussion and debate beforehand to neutralise the potentially explosive consequences before it is too late. At the beginning of the year, Armenia’s Foreign Intelligence Service already warned that there were already signs of domestic instability to come in 2025. The stakes have never been higher.