The Sahel region stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea and consists, according to the UN, of ten countries which sit, wholly or partly, within it: Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria Other neighbouring countries however, such as Benin, Togo Sudan and Central African Republic, due to their proximity, and to the fact that they increasingly share the same problems, are often included when the Sahel is discussed.

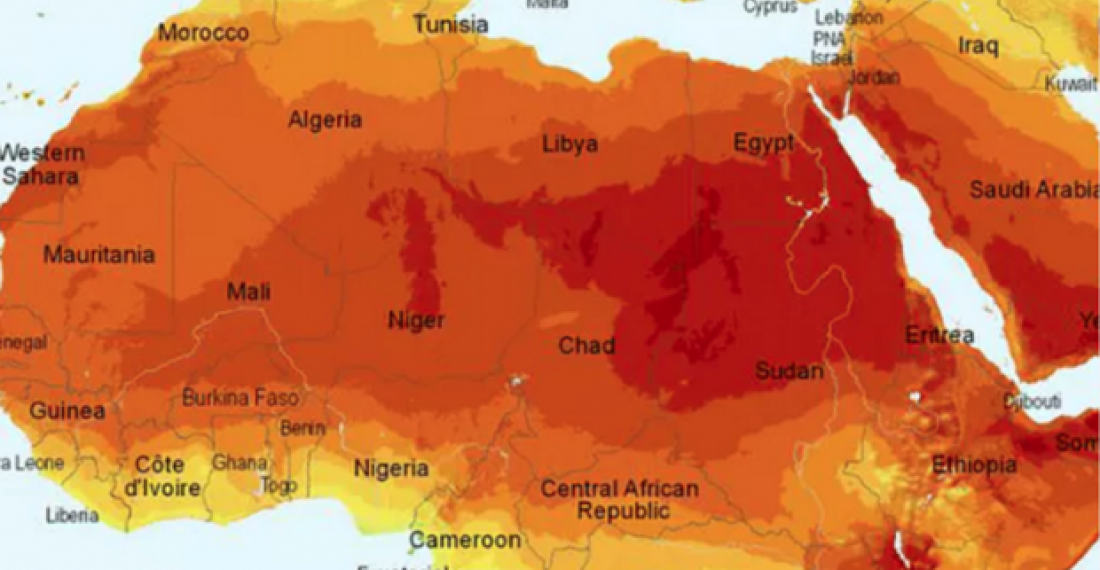

The Sahel is semi-arid grassland along the Sahara's southern edge. Its environment is not as harsh as in the Sahara but climate change is resulting in regular periods of drought, and other extreme weather conditions.

Three problems now dominate any discussion of the Sahel: conflict and insurgency; governance; and climate change and demography. The three problems are interconnected, and when you speak about one, you quickly have to move to the others.

Conflict and Insurgency

There are two main Islamist Groups, one linked to al-Qaeda, the Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM), and one to the Islamic State, IS-Sahel. They often fight each other. They also fight the governments of the region who they consider as their oppressors, and their allies, which until recently was France and the International community, which included the United Nations and the European Union. Lately, they are fighting the Russians who have replaced them, also accusing them of grave human rights abuses. In Mali and other parts of the Sahel the Islamist groups feed on the discontent of the Tuareg people, who have for many years struggled against the elites based in the South of the country, and foreigners perceived as helping them.

According to the Sydney-based think tank, the Institute for Economics and Peace, and their “Global Terrorism Index” the Sahel is the "epicentre of global terrorism" and now, for the first time, accounts for "over half of all terrorism-related deaths”, 3,885 people out of a worldwide total of 7,555 died in 2024.

The figure for the Sahel has increased nearly tenfold since 2019, as extremist and insurgent groups "continue to shift their focus" towards the region.

In Mali, after the French left in 2022, the international effort to fight the insurgency threat was spearheaded by MINUSMA, the United Nations Mission in Mali. In 2023 MINUSMA numbered nearly 16,000 personnel. Although most hailed from African countries there were large military contingents from Germany and China. MINUSMA was closed down at the end of 2023 by order of the new military government in Mali, that accused it of not fulfilling its task. Its exit was quite messy as insurgent groups tried to occupy its forward bases around the town of Timbuktu before they were handed over to the Malian army.

The region is awash with arms.

In his last years in power, the Libyan leader Muammar Gadhaffi changed the foreign policy and defence focus of his country. Having been snubbed by his Arab brethren Gadhaffi focused his attention on Africa, and built close relations with groups like the Tuareg that historically have close relations with Libya. At the same time, Gadhaffi changed his country’s military posture to one based on the concept of a people’s defence. Large quantities of arms were stashed in desert hide-outs in Southern Libya. When the Libyan civil war broke out large numbers of Tuareg, and others from across the Sahel, were brought as mercenaries to fight on the side of the Gadhaffi government. They were well-armed, and given access to the arms hideouts. When the Gadhaffi government collapsed these mercenary groups melted into the Sahara, taking a lot of arms with them.

Governance

In Britain, in the 1960s there was a joke that in African countries the president is the first soldier who wakes up in the morning and goes to the radio station to declare himself the country’s new leader. Africa in the 21st century thought that it had put these bad times behind it, and that the military would keep out of politics, but in the last decade the military coup has returned, and in the Sahel, it has returned with a vengeance.

Since 2020 there have been six successful coups in the core ten Sahel countries: two in Mali, two in Burkina Faso, one in Guinea and one in Niger. Military takeovers appear to have the support of the population. This is due to the incompetence and corruption of civilian governments, and their alleged cosy relationship with Western governments, particularly France.

One of the assertions of the military leaders was that the civilian governments were not doing enough to quell the insurgencies. Now they are realising it was not so easy. But the military regimes are digging in, and there is no sign they will return to the barracks any time soon.

Demography and Climate Change

The Sahel has some of the world's highest birth rates, and almost two-thirds of the population is under 25. The population of the six countries of western Sahel, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, and Senegal amounts to more than a hundred million.

The young population is restless. Many embark on the hard journey of crossing the Sahara on the way to Europe. The desert is more porous than it looks. But the migrants have to endure unscrupulous human traffickers in North African countries before doing the dangerous crossing across the Mediterranean.

Climate change is something very real for the people of the Sahel. The Sahara is creeping in making the life of the local population unsustainable. Fighting is these days as much about control over water as on other issues. According to most scenarios, temperatures in the Sahel will rise by at least 2°C in the short term (2021-2040), a rate 1.5 times higher than the global average.

Extreme weather events such as droughts and floodings are likely to be the norm.

Russia

The Sahel is a victim of a complicated global situation.

Russia has made a surprise appearance in the region. The military coups brought young leaders who were desperate for support. Western countries took their eye off the ball when the Ukraine war started in February 2022. The Russians promptly moved in to fill the vacuum.

Not even the turmoil in the Wagner Group could stop the Russian advance. Today, a trimmed down Wagner presence still holds sway in places like the Central African Republic. But in most of the Sahel Russia is now more directly involved, through its Africa Corps. The Corps operates under the orders of the Russia military intelligence, the GRU. A GRU General, the infamous Andrei Averyanov, oversees the work of the Corps. So far they have not been able to reverse the advances of the Islamist groups.

European Union

Up to February 2022, the Sahel was a priority for the European Union (EU). The war in Ukraine weakened the EU’s resolve, and emptied its war chest. The military coups took away the narratives of support for emerging democracies, and brought to power governments that were hostile to Europe and all it stood for. The US presence shrank, and will probably shrink further.

In Brussels they are not good at handling failure, so failures are forgotten and few lessons learnt. The Sahel is a case in point. It started off as a migration problem, then there was talk of a coordinated approach, but that now seems to be forgotten.

Yet the Sahel is important for Europe. It is the EU’s soft underbelly and engaging with the region and its problems is not a choice, but a must.

The EU has a new Special Representative for the Sahel. Mr João Gomes Cravinho took up the duties of EU Special Representative for the Sahel at the end of last year. His mandate is “to lead the EU's contribution to regional and international efforts for lasting peace, security and development in the Sahel”. He also coordinates the EU's comprehensive approach to the regional crisis, on the basis of the EU Strategy for Security and Development in the Sahel.

He has had the period from Christmas to Easter to get on top of his brief. As former Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of Defence of Portugal he knows Brussels well. It is important he gets Brussels to focus on the Sahel’s problems, and their solutions.